The beginning of the second semester is accompanied by the eternal debate on the impact of the policy of social inclusion by establishing quotas for less favored classes as a criterion for entry into federal universities. This debate has become more heated by the recent decision of the US Supreme Court, which determined the end of the quota program in the United States for university entrance, in force since 2003, on the grounds that the US Constitution guarantees equal protection to citizens. The Supreme Court's majority decision reflected an existing division in American society.

In Brazil, this week, the Chamber of Deputies approved the renewal of the quota law with a forecast for a new review in 2033.

Studies show that the average performance of students benefiting from affirmative action programs is lower than that of other non-quota students. This should come as no surprise. If it were so easy for quota students to outperform non-quota students, no one would be arguing for the existence of quotas. It is precisely because they are worse that the idea of affirmative action arises. Nor is it the case to take these results as an indisputable demonstration that quotas should be rejected out of hand, since they would only serve to undermine the meritocracy of the entrance exams.

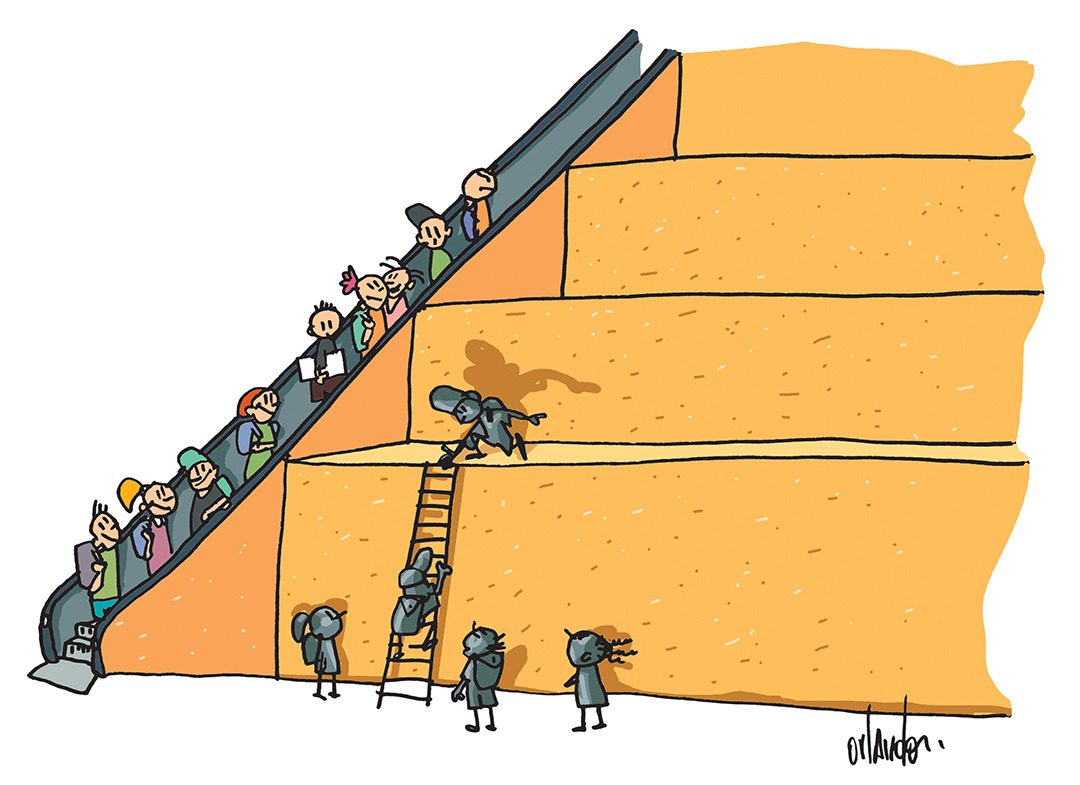

The difficulty surrounding quotas stems from the fact that universities play a dual role. They have become the main factor of social ascension in the modern world and, in addition, they have the mission of training the professionals who will, in the near future, be at society's disposal. While the first criterion easily admits a more social justice-oriented approach, the second would naturally recommend a stronger adherence to academic excellence. The challenge is to find a way to reconcile the two principles. The answer certainly does not lie in raising the number of places exclusively for affirmative action minorities, currently at 50%. The excessive number increases the gap between quota and non-quota students, inflating the price of inclusion.

For those who understand that merit should always prevail, the question remains: what is the merit?

Eduardo Giannetti recalls that inequality poses an ethical problem depending on how it was established. For him "the crucial question is: does the observed inequality essentially reflect the differentiated talents, efforts and values of individuals or, on the contrary, does it result from a game rigged at the origin - from a profound lack of equity in initial living conditions, from deprivation of elementary rights and/or from racial, sexual or religious discrimination?".

The American philosopher John Rawls goes further. For him, natural aptitudes are no "fairer" than the birthrights of nobility or the advantages of growing up in a wealthy family. For the philosopher, attributes such as strength, intelligence and beauty would be an undue prize, since they result from random combinations of genes, not from individual virtues. Therefore, according to Rawls, if it is unfair to discriminate against someone because of the color of their skin, it is unfair to favor someone else because they were lucky enough to be born with the right quality at the right time.

In this way, the very idea of merit does not seem to hold if we presuppose a more absolute notion of justice like Rawls. Pragmatically, I understand that it is natural to hire someone based on their academic performance. The problem is that it becomes more difficult to equate the notion of meritocracy with that of justice.

The solution lies in improving the level of basic schooling.

One of the characteristics of academic knowledge is that students only progress well when they have mastered the previous stages. Certain subjects, such as mathematics, are simply impossible to progress without knowing the classic operations. No wonder, it has recently been found that mathematics teaching in Brazil has been depleting year after year. Thus, wanting the entrance exam to be the only element of selection at the entrance to universities is the same as accepting to put jiu jitsu fighters in the ring, one holding a white belt and the other a black belt, and thinking that the result could be different than the massacring victory of the black belt.

Thus, the right place to combat the knowledge gap is the early years of primary education. Education policy should favor free basic education during the period of cognitive formation and charge tuition fees at universities, even public ones, as a measure of social justice.

We know that the state cannot guarantee free study for all in academic completeness. At the same time, if there is equity in basic education, it becomes more palatable to reconcile work and study, and with this, even the less favored would be able to pay the tuition fees of higher education. Prioritizing budget money to subsidize free public universities, to the detriment of better basic education, is a policy that I cannot understand.

With greater inclusion and quality basic education, the learning gap between candidates at the entrance exam would be smaller and, consequently, the chances of reducing the number of social inclusion quotas in universities would be greater.